Within the past decade, social media has become one of the most widely used marketing tools that are consumed by numerous businesses to promote their brand identities. With the assistance of social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter, businesses and organisations can communicate and interact with their customers in a way that has never existed before. However, businesses must learn how to appropriately and effectively utilise these networked publics, as there are often undesirable consequences from poorly executed social media promotion (Boyd, 2010). This critique will explore Calvin Klein’s #mycalvins social media campaign. Factors that contributed to the ‘social media fail’ will be discussed, which will also be followed by recommendations for the company.

In 2016, Calvin Klein launched their Spring collection with a star-studded social media campaign. Featuring various celebrities, the campaign launched via Instagram, consisting individual photos of the celebrities wearing Calvin Klein apparel with the strapline “I____ in #mycalvins” overlaid onto each image. For example, Justin Bieber “dreams” in his Calvins and Kendrick Lamar “reflects” in his (Campaigns of the World, 2016). Despite the campaign achieving vast success, with 4.5 million interactions between users after just four months of the tag launching (Leo, 2016), the campaign has received unpleasant backlash after some of the advertisements were released.

The company put up a billboard in Soho, New York City which features a provocatively-posed image of actress Klara Kristin in her Calvin Klein apparel with the text “I seduce in #mycalvins”, directly next to male rapper Fetty Wap with the text “I make money in #mycalvins” (Campaigns of the World, 2016). Lingerie company ThirdLove’s CEO Heidi Zak argued that the poorly paired ads perpetuate sexist 1950s stereotypes about men and woman, propagating that women are nothing more than sexual objects, while men are the breadwinners (Stern, 2016).

In another Calvin Klein series of images from the #mycalvins campaign, the company has made a similar mistake, in which they took it on a highly-sexualised theme. The most provocative picture in the series features an ‘upskirt’ photograph of actress Klara Kristin looking down with the strapline “I flash in #mycalvins”. The photo was posted along with the comment: “Take a peek: @karate_katiaphotographed by @harleyweir for the Spring 2016 campaign. #mycalvins” (Birchall, 2016).

Immediate and disturbed reactions from a huge amount of Instagram and Twitter users had surfaced, as several commenters slammed the photo as “disgusting”, “trashy and repulsive”, “pathetic” as well as “misogynistic” (Birchall, 2016), while some pointed out that the photo was “pornography” (Hudson, 2016). Some suggested that the girl in the photo appeared to be underage in the photo, which would appeal to paedophiles, which then the company was accused of hypothetically peddling in child pornography. For example, one twitter user tweeted “@CalvinKlein Shame. Giving every paedophile a peek up a 12-year-olds skirt. Just wrong” (Hudson, 2016).

Several practical and theoretical misunderstandings of social media strategy are apparent in these few images for this campaign, which contributed to this social media “fail”. When designing a social media strategy, general considerations include: purpose, research, platforms, reporting, incentives and resourcing (Cassidy, 2017). In this case, the lack of research has contributed to the fail as Calvin Klein had failed to research into their target audience and certain opinions they might have before launching the campaign on social media. Within the recent decades, sexism and women objectification have been heated topics in the modern society as an increasing amount of people are starting to have opinions in this subject, in which viewpoints like “women and men are equal” and “women are not sexual objects” are forwarded to promote gender equality and the breakdown of gender stereotypes across the world. Therefore, ads that may possibly include a sexism message or anything similar in that nature should not have been released.

Moreover, factors such as cultural positioning, sociotechnical convergence and new media cultures affect our ethics with new media (Cassidy, 2017). In this modern society that we are living in where anti-sexism is becoming more dominant, new media has been culturalised and the way many audiences view ‘pornography’ has been distorted. Social and technical networks are merging together due to sociotechnical convergence; therefore, the way social networking sites is shaped has also altered. Some users might find images from the ads provocative and some might not see a problem at all. However, Calvin Klein should not eliminate the possibility that some of their audiences might be offended by the ads.

On the other hand, it had become well established that nation states had both the right to regulate, and an interest in regulating the internet as it had become part of our daily social life (Edwards 2009: 626). Consequently, existing laws and regulations can be applied to social media. Some social media users suggested that the ‘upskirt’ image featuring Klara Kristin was ‘pornography’. Calvin Klein might have violated the ‘Terms of Use’ on social media for posting sexual content as it is mentioned in the document that the content posted must not include indecent, obscene, pornographic or otherwise inappropriate language, information or other content (Queensland Law Society, 2017). However, it was assumed that the company escaped the consequences of it due to their global popularity, as one person wrote “It is illegal to take a picture of someone under their skirt. How amazing that your pornographic image (which would be illegal if it were someone else) is what you have reverted to sell your items” (Verhoeven, 2016). The company should have considered the appropriateness of the content they are posting and the possibility of their content being restricted or deleted under internet governance.

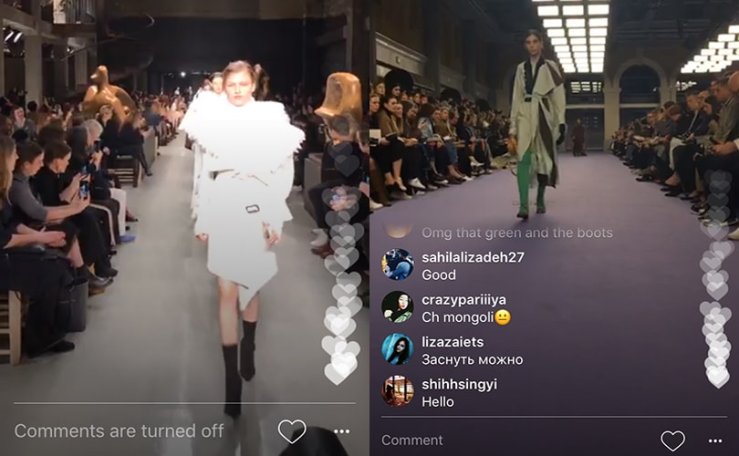

Calvin Klein has also taken advantage of the affordances, particularly the spreadability and scalability of Instagram and Twitter. Using the hashtag #mycalvins, the company aimed to potentially reach to a wider audience and gain popularity for their brand campaign. However, the scalability of content in networked publics have been underestimated and unacknowledged. Reactions can’t be predicted as people choose what to spread and how they spread it and it is one of the key characteristics of today’s participatory culture (Jenkins 2006). Therefore, users can spread and amplify negative content using hashtags and they can easily be searched, which further emphasises the significance of ensuring a suitable and professional response framework. In this case, some twitter users include the #mycalvins hashtag to spread negative feedbacks in respond to the over-sexualised ads, as seen in the tweet below:

To avoid the nasty situation this campaign has created, many social media strategies could have been implemented to potentially improve the campaign’s success and to eradicate negative outcomes. Undertaking quality research is one of the most significant strategies as the more you know, the more relevant you can be (Cassidy, 2017). Specifically, surveys and interviews could be undertaken for a data analysis for the campaign development. Without decreasing the level of engagement with customers, this would avoid public shame and damage to the brand reputation. Ensuring the company is delivering appropriate messages would also essentially change how the brand is being presented and the way audience vision it. Acknowledging beliefs or opinions target audience might have would help to avoid major backlash as it is said that the internet will foster a generation of users that are more socially aware and culturally sensitive by 2020 (Khor and Marsh, 2006). As communication is becoming increasingly more fragmented and intimate, it is key to know who holds the power to spread the content posted. Although hashtags are designed to spread content on social media, it is fundamental to be aware of the affordances these networked publics have as they tend to highlight both positive and negative issues to the public. The company could focus on creating a campaign that does not require much user participation but would still engage with audience and gain popularity, for example sponsoring celebrities to promote their apparel on social media which might influence what the audience consume. To build a respectable reputation and ensure success, everything should be perfectly planned in every aspect and risks should be carefully assessed.

It is evident that there are several complexities surrounding use of social media in professional practice that Calvin Klein have misunderstood which contributed to the ‘fail’. Recommendations and strategies which might have avoided the mistakes that was made have been suggested for the company’s future success. It is only right to have a change in plan as new media culture and consumer ethics will only continue to change in the evolution of technology.

Resources

Boyd, d. (2010). Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics and Implications. In d. boyd, Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites (pp. 39-58).

Birchall, G. (2016). Calvin Klein blasted online over ‘trashy and repulsive’ upskirt Instagram advert. [online] Adelaidenow.com.au. Available at: http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/lifestyle/fashion/calvin-klein-blasted-online-over-trashy-and-repulsive-upskirt-instagram-advert/news-story/2d4250e066fda867211e6d2d5f7ec596 [Accessed 30 May 2017].

Campaigns of The World. (2016). Calvin Klein Spring 2016 Ad Campaign – #mycalvins. [online] Available at: https://campaignsoftheworld.com/outdoor/calvin-klein-spring-2016-ad-campaign-mycalvins/ [Accessed 30 May 2017].

Cassidy, Elija. 2017. “KCB206 Social Media, Self & Society: Week 8 .pptx” Available at: https://blackboard.qut.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-6789699-dt-content-rid-8347265_1/xid-8347265_1 [Accessed 29 May 2017]

Cassidy, Elija. 2017. “KCB206 Social Media, Self & Society: Week 11 .pptx” Available at: https://blackboard.qut.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-6810569-dt-content-rid-8594913_1/xid-8594913_1 [Accessed 29 May 2017]

Edwards, L., 2009, ‘Pornography, Censorship, and the Internet’, in L. Edwards and C. Waedle (eds.), Law and the Internet (3rd Edition), Hart Publishing, Oxford: 623-670.

Hudson, J. (2016). Calvin Klein Under Fire for Overtly Sexual Ad Campaign: ‘This Is F*cking Disgusting’. [online] Breitbart. Available at: http://www.breitbart.com/big-hollywood/2016/05/11/calvin-klein-overtly-sexual-ad-campaign-disgusting/ [Accessed 30 May 2017].

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture. 1st ed. New York [u.a.]: New York Univ. Press.

Khor, Zoe and Peter Marsh. 2006. “Life Online: The Web in 2020.” Social Issues Research Centre on behalf of Rackspace Managed Hosting. Available at: www.sirc.org/publik/web2020.pdf

Leo, S. (2016). #MyCalvins campaign takes over the internet. [online] Truly Deeply – Brand Agency Melbourne. Available at: http://www.trulydeeply.com.au/brand-engagement/mycalvins-viral-campaign-advertising-brand/ [Accessed 30 May 2017].

Queensland Law Society. (2017). Social media usage. [online] Available at: http://www.qls.com.au/About_QLS/Site_policies_disclaimers/Social_media_usage [Accessed 30 May 2017].

Stern, C. (2016). Calvin Klein removes controversial billboard saying Fetty Wap is ‘making money’ while a scantily-clad actress ‘seduces’ after furious protesters labeled the campaign ‘sexist’. [online] Mail Online. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-3502932/Calvin-Klein-removes-controversial-billboard-saying-Fetty-Wap-making-money-scantily-clad-actress-seduces-furious-protesters-labeled-campaign-sexist.html [Accessed 30 May 2017].

Verhoeven, B. (2016). Calvin Klein Blasted for ‘Soft Porn’ Up-the-Skirt Ad: ‘Child Porn,’ ‘Disgusting,’ ‘Creepy’ (Photo). [online] TheWrap. Available at: http://www.thewrap.com/calvin-klein-upskirt-underwear-ad-child-porn-disgusting-creepy-instagram-twitter/ [Accessed 30 May 2017].